I am already seated in the plush surrounds of the Hotel Windsor’s grand salon, when Phillip strides into the room. He is running a bit behind time. Unhappy with the table we have been allocated, Phillip requests a corner location.

Phillip is apologetic as he explains, “I was trained in the French manner – it is all about presentation. We will be seen to greater advantage looking out into the room like this.”

He continues, “You see? It permeates all aspects of life. Whether it be making hats or whatever, always put your best foot forward. I know it is a little old fashioned these days, but it is a hard habit to break.”

I ask when Phillip first became interested in millinery. “I suppose when I became interested in glamorous things. Will I say 4 or 5 years old?”, he muses. “But I didn’t actually think of it as an independent activity until I went to work in the workrooms of William Beale, Mr Individual Hats. He was perhaps the only truly spontaneous person I have ever met. Proof that spontaneity can be life threatening. His relationship with electricity, for instance was quite… well, casual. He ran the only millinery room in Melbourne in the 80s and I learnt to make hats there.”

Phillip adds, “The Head Milliner, Phyl Ross, and I used to talk about ‘thinking milliners’. It was a great training. ‘Thinking milliners’ are always looking to innovate and improve techniques and aesthetics and I have found that it makes one experiment with technique and question convention. It also tends to lead one into trouble. You get ideas above your station.”

When I remark that Phillip’s career in the hat world has been quite varied, he isn’t very forth coming. “Well, I have always gone where the work is… but I have done nothing other than make hats from the outset.”

I resort to my research to ask about his time in London and later as Head Milliner at the Australian Ballet.

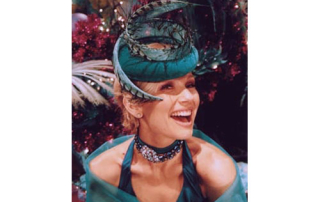

“In London I worked for theatre, films, television, as well as fashion. I think that people were amused by an Australian male as an arbiter of questionable taste back in the mother country. Australian ingenuity intrigued them too. I would make my own hat trimmings from off cuts, whereas the milliners there were used to copious bounty and reached into the box for French roses and curled plumes and the like. I was very useful for any film set during the austerity years of World War II.”

About the Australian Ballet, Phillip noted, “Yes, a person really needs to be a problem solver to do that job. Mind you, nothing today compares to the work that was done there in the fledgling years of the early 70s. The makers had the genius spark then.”

“You are known for the intricacy of your hats”, I remark.

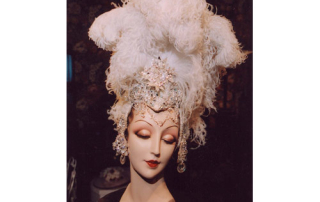

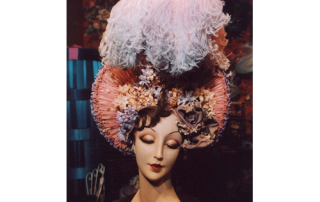

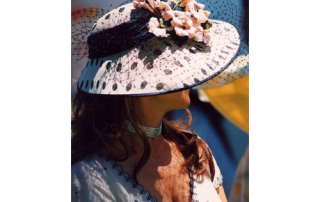

“Yes, during the 90s I experimented quite a lot with complexity of making. So that the hat needed little embellishment beyond the textures and techniques employed. Consequently it was not uncommon for brims to be made of 4 or 5 separately blocked pieces and crowns of 2 or 3 different pieces. It seems so overblown today, but that sort of showiness was the vogue then. Technically it was very challenging. I had to change my approach, however, when I saw a Donna Karan suit that looked like it had been in a shipwreck. When the client collected the hat, she felt that the hat put the suit to shame. It was quite the reverse. It was a seminal moment in my work. Fashion had shifted and so must my eye and taste. Fashions change. Just like all those adorable vintage styles and trims that have been popular for the last 2 years… suddenly monotonous!”

I asked Phillip to expand his thoughts on where modern millinery is heading. “The business of millinery was until recently the actual making of hats, but the production work that is coming out of the factories of Asia forces us all to re evaluate our role. Hats from Shanghai or Manila are equally pulled over the block by hand, etc., etc. If the factory owners in Asia were more savvy to western taste, their product could well dominate the market. I think that hats in the future will become quite literally party hats.